Preview

Creation Date

1908

Culture

American

Medium

Photographic print on cardboard

Dimensions

7 ⅞ × 10 in.

Credit Line

Gift of Sarah Blick, 2015

Accession Number

2015.192.2

Description

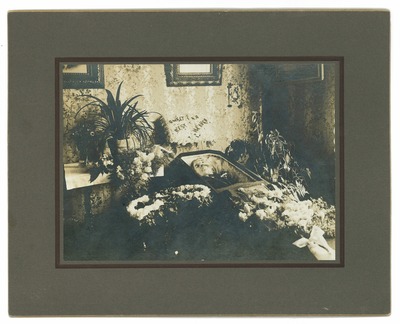

Post-mortem photography was a way for families in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to obtain a visual remembrance of their loved ones. For most families in the early nineteenth century, these portraits were the only personal photographs they owned. Post-mortem photographs were kept within the family and hidden within luxurious daguerreotypes, it was uncommon to share these personal photographs although they were once one of the most popular photographs to take in America. Early forms of “mourning portraits”creatively staged the deceased outside of their coffins to look alive or sleeping. In an eerie composition, the body would be posed with his or her living family members. Towards the beginning of the twentieth century, funerary photographs became less confrontational and religiously symbolic and the process was outsourced by the undertaker. The photograph would be taken before or during the funeral under the supervision of a professional undertaker. Later post-mortem photographs generally left the body in a closed coffin surrounded by elaborate flower arrangements. Despite losing its theatrical quality in the early 1900’s, mourning portraits maintained their retrospective sentiment in new ways. In the first photograph (2015.195), the coffin of Tilda Aronson is beneath the altar signalling a powerful memento mori. The coffin is centered at the front of the church to symbolize “A Service of Death and Resurrection." It was commonplace in the United Methodist Church to march the casket to the altar before burial. In this photograph, Tilda’s casket is closed and is adorned by bouquets of blooming lilies. This photograph (see also 2015.192.1) is of Tilda’s husband, Anders Gustaf Aronson, in a decorated funeral home. Aronson’s casket is partially open with crowding flower arrangements surrounding him. “sweet rest in heaven” from the Book of Revelations is written above his head in flowers. This verse states that “the dead from now on die in the Lord” granting them an immortal soul. These words were sung as mourning hymns at Methodist funeral services. These two photographs are excellent examples of the transition between the earlier and later styles of memorial portraiture. The family carefully positioned both photographs to not only reminds them visually of their loved one but also to quell anxieties of the finality of death. The words written on the wall in the second photograph and the holy altar in the background of the first photograph romanticize the prospects of heaven and provide assurance of their well-being. Post-mortem photography was treasured as a reminder of their deceased loved one and a humbling force to which they were able to memorialize and hold onto forever. Moreover, memorial portraits were traditionally more expensive than ordinary photographs because it represented the loss of an irreplaceable identity. A unique expression of individual identity and self worth was emphasized in American funerals such as the Aronson’s due to their idealistic precedent of individual expression. Death represents society’s limited agency in preservation. Small tokens such as memorial portraiture give off the illusion of immortality. —Claire Koelling ('19)

back